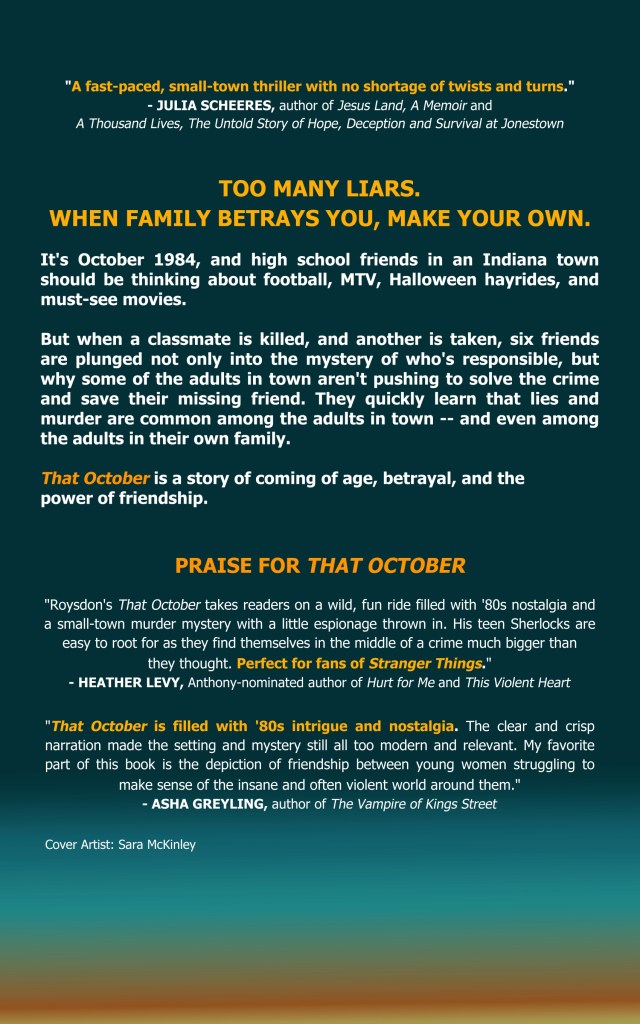

The bright young faces in this photo belong to David and Julia.

The bright young faces in this photo are of Julia and David as portrayed by Ella Anderson and Xavier Jones.

My friend Julia Scheeres’ 2005 memoir, “Jesus Land,” is being made into a movie. If it’s anything like Julia’s book, the movie – directed by Saila Kariat – will be poignant and harrowing and heartfelt and, yes, controversial. Julia’s memoir is routinely banned because she tells the truth about the fundamentalist Christian life.

I’ll give you the shorthand version of why we should all care about “Jesus Land,” and why you should read Julia’s book and see the movie when it comes out. First, a little background.

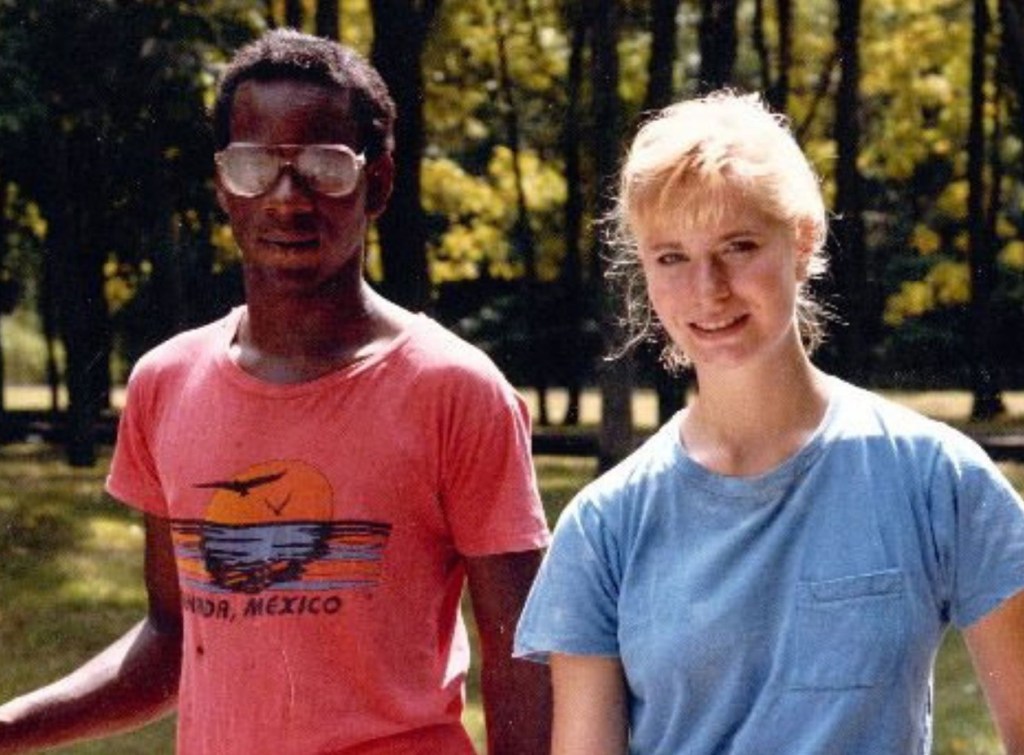

Julia and I grew up in Indiana at about the same time. In the 1980s. I lived in Muncie and she lived in the Lafayette area. Her parents were abusive religious fundamentalists – my family was Baptist but never abusive when I was growing up. Julia’s parents ended up sending Julia and David to the Dominican Republic to a teen concentration camp run by an Indiana church.

I didn’t know Julia until about 20 years ago, when she contacted me from her home in California to ask if that church was undergoing a rebirth in Indiana.

I spoke with Julia and other survivors of the church gulag and, along with a small group of reporters and editors, wrote extensively about their experiences and the modern-day church and whether it was still sending, at parents’ expense, kids out of the country to hellholes, where they were abused and made to work.

I disappointed Julia back then because my editor at the time was so afraid of upsetting the church and the local chamber of commerce that they gutted our stories.

Julia’s “Jesus Land” had come out the year before, and it told the story better than we could have anyway.

Julia and I became friends – we never met but kept up to date on each other’s families and kids on Facebook – and I wrote about “Jesus Land” again in 2021, when I interviewed Julia for an article about fundamentalist groups that were pressuring Indiana schools to ban the book. It’s something that Julia has grown accustomed to: “Jesus Land” is among books regularly banned because it dares to tell the truth about the religion-based “troubled teen industry,” and how there’s money to be made by pseudo-religious organizations that incarcerate “troubled” young people.

The two of us also spoke while I was working on, shortly after that time, another story about money flowing to the troubled teen industry in Indiana. Julia encouraged me to pursue the story and read drafts of it, which I worked on on a freelance basis for more than a year. Ultimately, the cowardly editors of a major newspaper spiked my story but kept all my research – legal documents, video depositions, reports – and, a year later, did their own story. It remains a very bitter end to my newspaper career.

I’ve moved on from those disappointments to other forms of writing, and Julia has moved on in spectacular fashion: She’s written and published two more books, and now “Jesus Land” will move from the realm of New York Times bestseller to big-screen film.

Julia and David’s story, so movingly told in “Jesus Land,” will find a whole new audience.

Julia, always gracious and kind, was the first person I thought of when I thought of writers who could read my new 1984-set crime novel THAT OCTOBER. I hoped she would appreciate its story of Indiana teenagers grappling with injustice and forces beyond their control. Her comments about the book are prominently displayed on the back cover.

Thank you, Julia. I’m so happy for the movie version of your book.