This is sad news. Not nearly as sad or despairing as much of what we see in the news in recent years, but sad nonetheless.

The mass market paperback is dead.

This might not surprise some of you who react, “Yeah, I know, I haven’t seen one in a bookstore in a while,” or “What is a mass market paperback?” For those young enough that they don”t remember the mass market paperback, I’m fearful you’re reading this past your bedtime.

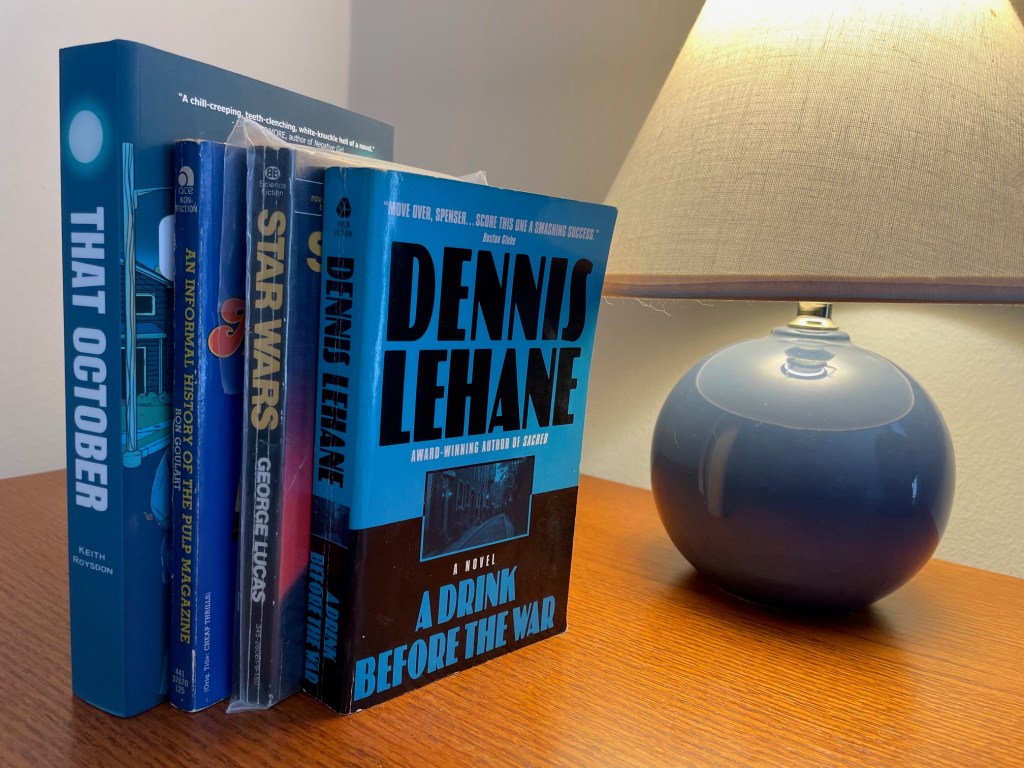

Publishers Weekly likely broke the news to most of us who remember mass market paperbacks – I’m going to refer to them as just paperbacks pretty soon now, for expediency’s sake – in a December article that noted that the ReaderLink company said it would no longer distribute mass market paperbacks. The format’s share of the market had dropped dramatically over the past couple of decades as larger-format paperbacks, sometimes referred to as trade paperbacks, and ebooks had usurped the market that had been dominated for many decades by mass market paperbacks.

Paperbacks had been the format of choice for much of the 20th century. They were less expensive than hardbacks but more cheaply made and thus less durable. But they had an ease of use, a convenience and an aura that were hugely appealing to most of us who were buying books in the last few decades of the past century. In 1966, the Beatles released a single, “Paperback Writer,” that ironically but lovingly paid tribute to the format. You didn’t hear the Beatles singing about their desire to be a hardcover writer, did you? No you did not.

As many know, paperbacks – measuring about 4 inches by 7 inches, just the size to fit in a pocket so you could always have a book at hand – were introduced before mid-century but might have become the hottest book trend ever in the 1940s and 1950s, continuing that hot streak into the 1960s and 1970s.

Paperbacks went to our workplaces, where they were handy to read on our lunch hour. They went on our commutes, where they occupied many a train and bus rider. They went to school and war in backpacks and pockets. They went everywhere, in part because of their convenient size and in part because they were so incredibly inexpensive to buy. I just looked at one of my oldest and most rare paperbacks this morning, a copy of Harlan Elliison’s “Rockabilly” from 1961. The cover price was 35 cents.

The vast majority of paperbacks I bought in the late 1960s and 1970s were priced at 65 cents, 75 cents, 95 cents. Paperbacks I bought into the 1990s were still only a few dollars, inexpensive compared to hardcovers and large-format trade paperbacks that, in my buying experience, were confined to scholarly or pop-culture works about movies, TV shows and comic books. At least that’s what still fills my bookshelves. I recently noted my copy of “The Marx Brothers at the Movies,” a 1975 Berkley trade paperback of a 1968 hardcover original, cost me just $3.95.

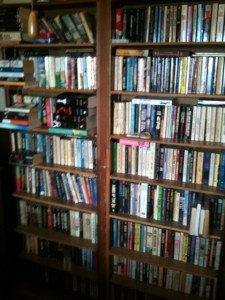

I have hundreds of books. Some are of recent vintage but the majority date from the 1960s to the 1990s. Among people my age, that’s probably not uncommon. Paperbacks entertained and informed us. Some of my favorites are early Stephen King novels and short story collections, the work of Robert A Heinlein and Ray Bradbury and Dean Koontz.

And I wasn’t alone. Publishers Weekly says 387 million mass market paperbacks were sold in 1979, compared to 82 million hardcovers and 59 million trade paperbacks. The 1975 movie tie-in of Peter Benchley’s “Jaws” sold 11 million copies in its first six months

Publishers Weekly notes that the paperback began losing its share of the market with the growing popularity of trade paperbacks and ebooks, the latter of which boomed in the early 2000s. And of course the shrinking number of bookstores – a trend which has, happily, reversed course – further eroded paperback sales.

Folks who’ve read this site before know I’m a fan of bookstores, especially used bookstores, and they’ll forever be a place to find books in all formats, including the once-beloved paperback, also known as the mass market paperback.

That’s where you’ll find me, looking to recapture a little of a past that’s quickly disappearing.